Obtain news and background information about sealing technology, get in touch with innovative products – subscribe to the free e-mail newsletter.

Japan Hydrogen Olympics 2020

Japan was the first industrialized country to adopt a national hydrogen strategy. The Olympic Games are expected to help secure a leading position for the nation in the technology.

The Olympic Games are always an occasion for statements beyond pure sports competition. When Tokyo hosted the games in 1964, Japan presented itself as a high-tech nation with the help of electronic time measurement and the Shinkansen high-speed train. For the upcoming games, the organizers want to repeat this feat with robots and autonomous taxis. But their efforts are especially inspired by the dream of protecting the climate: The country wants to position itself as the torchbearer for a global hydrogen economy, in the truest sense of the word. For the first time, the Olympic flame will burn hydrogen. It will come from the Fukushima Prefecture, the scene of the nuclear catastrophe of 2011, and will be extracted from water with the help of solar energy. An official of Japan’s powerful Agency for Natural Resources and Energy stressed the symbolism of the arrangement. “This will heighten the public’s awareness of the important role that hydrogen will play in the future.”

By 2025, the number of fuel cell vehicles in Japan alone is expected to rise from 3,600 currently to 200,000

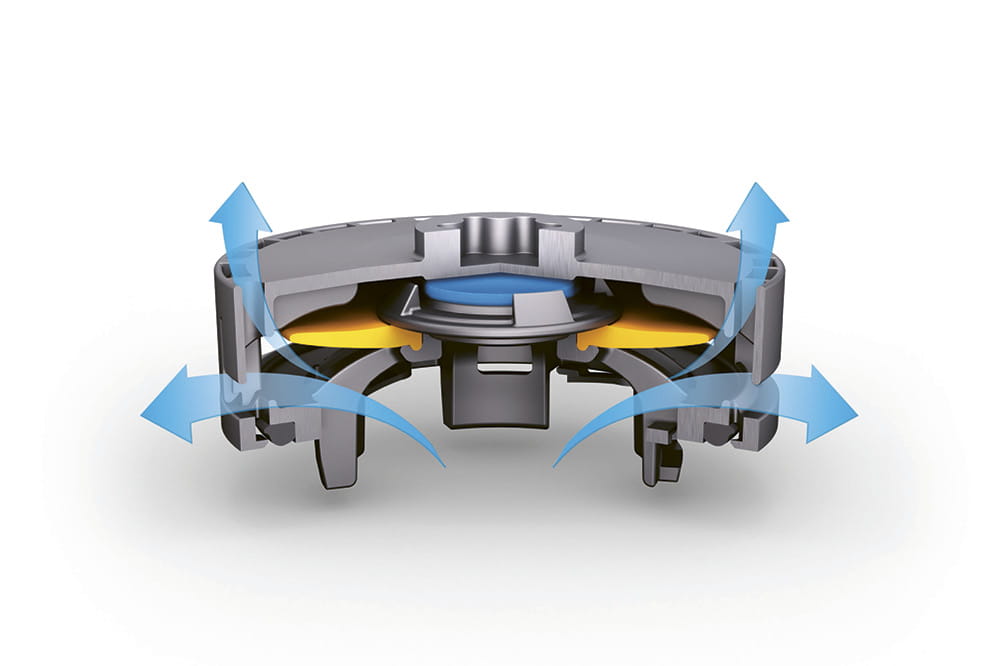

Japan’s government sees itself as the world’s pioneer in generating electricity from hydrogen – and doing it without CO2 emissions. It works like this: Hydrogen and oxygen enter into a chemical reaction inside the fuel cell. Heat and electricity are the result, with water as the sole byproduct. “Japan has led the world in the practical application of fuel cell technologies, for example, in the commercialization of fuel cells for cars and residences,” the official said. To lock in the country’s lead, the government adopted a national hydrogen strategy in 2017, and other countries followed suit. But Japan still stands out for its detailed, ambitious objectives as well as its close collaboration between industry and the country’s political leaders.

Japan’s Global Plans

The government has not limited its vision to Japan. By 2050, it wants to turn hydrogen into a real alternative to fossil fuels worldwide. On the one hand, over the course of this decade, it wants to build up a global supply chain capable of producing and distributing hydrogen on an industrial scale. On the other hand, it wants to quickly create mass markets to rapidly reduce costs, which are still high. Vehicle manufacturing is an important sector in this regard. By 2025, the number of fuel cell vehicles in Japan alone is expected to rise from 3,600 currently to 200,000 and to 800,000 by 2030. Moreover, 1,200 buses and 10,000 forklifts are due to be powered with electricity from fuel cells.

Japan is also taking aim at energy production. Fuel cells are already providing electricity and hot water to apartments and individual homes, a market that requires no subsidies. Since 2009, 300,000 of the block heat and power plants, dubbed “Ene-farms,” have been sold. In these cases, the “energy farms” still obtain their fuel from city gas, which has mostly been obtained from coal gasification. That is because the infrastructure for pure hydrogen is still insufficient. In 2021, the market leader Panasonic will introduce the first fuel cells to use pure hydrogen. If planners have their way, 5.3 million energy farms of both types will be in operation in 2030.

The national strategy also puts demands on electricity suppliers. Over the next ten years, they are supposed to build hydrogen power plants with an output of 1 gigawatt. That more or less equates to the capacity of a nuclear reactor. By then, the price of hydrogen is expected to fall 70 percent to $3 per kilogram. In 2050, the lightest chemical element is due to contribute as much as 30 gigawatts to Japan’s electrical supplies.

Pioneer for an Emission-free Society

But the hydrogen plans had a difficult birth, Toyota engineer Katsuhiko Hirose recalled. He himself became a notable hydrogen convert in Japan. Toyota and Honda, which both sell fuel cell vehicles, had to put massive pressure on planners in the country’s economics ministry, to shift their focus away from electric-car batteries. His own experience likely made it easier to convince them. After all, Toyota had selected him, of all people, the co-developer of hybrid cars, to design the automaker’s fuel cell car, the Mirai. Until that point, he considered battery-electric and hybrid cars to be the quicker and better solution, not least of all because of high energy losses associated with hybrid propulsion and the lack of infrastructure. But Hirose is now singing a different tune: “You need a holistic vision for the de-carbonization of all society. We can’t just handle the transportation end emission-free. We want to build our cars with neutral emissions as well.” His message: If you want a zero-emission society, you need hydrogen – and a lot of it.

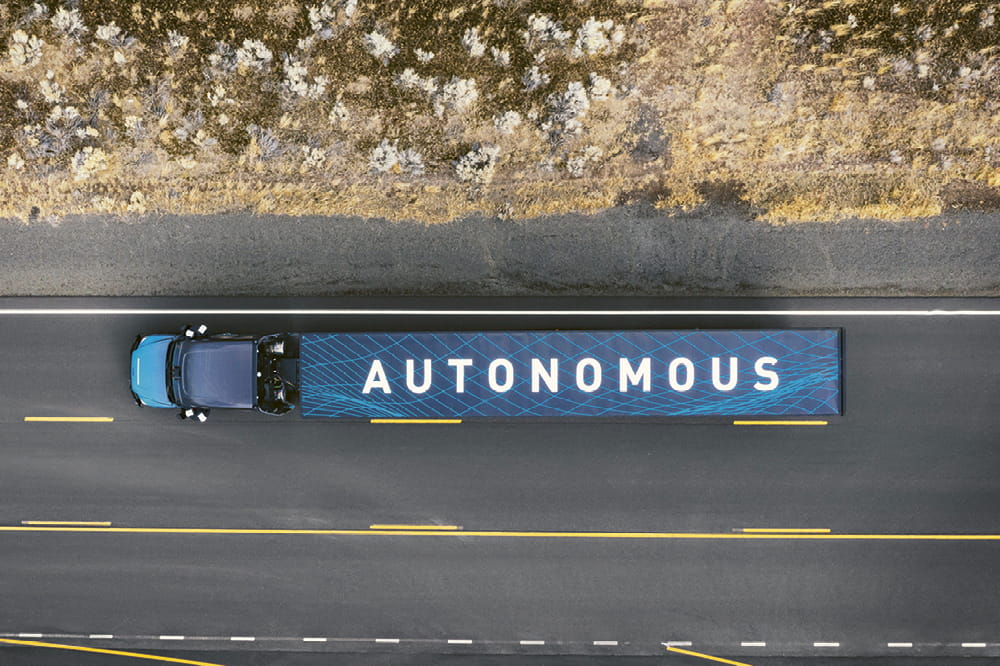

Like Japan’s steel companies, Toyota is developing hydrogen-fueled blast furnaces for its factories. The country’s energy expert also points to hydrogen’s role as a portable, combustible energy storage medium. Operators of solar and wind power facilities can produce hydrogen with their excess electric current, which can be used in hard-to-electrify applications elsewhere – in trucks, ships, steel production and oil refineries, for example.

The Search for Hydrogen Suppliers

But the real strength of Japan’s strategy is that it has become a national movement, with political leaders and industry driving each other. The government is going all out to recruit hydrogen suppliers on a global scale. At the end of 2019, the first hydrogen transport tanker was built and launched by Kawasaki Heavy Industries.

If you want a zero-emission society, you need hydrogen – and a lot of it.

Katsuhiko Hirose, Toyota engineer to design the automaker’s fuel cell car, the Mirai

For imports, the government has resorted to a strategy that has raised some eyebrows among climate activists. For example, starting this year, Japan is getting coal-generated hydrogen from Australia, and hydrogen produced from natural gas is due to be imported from Southeast Asia. It is only later that Saudi Arabia is expected to become a major supplier of “green” hydrogen produced from water with electrolysis, powered by electric current from renewable energy sources.

Japan Initially Resorting to Hydrogen from Coal

Japan’s government is defending its use of coal and natural gas – along with its methods of carbon dioxide storage – as a key intermediate step toward a more rapid conversion to green hydrogen. The calculation: The more profitable the enterprise, the greater the incentive for governments, companies and investors to shift capital into innovations and to develop common rules and technological standards. With the government’s help, Japan’s industrial sectors are now pressing ahead. In 2018, automakers teamed up with natural gas and oil companies, investors and other enterprises to form the “Japan H2 Mobility” company to fund the construction of hydrogen filling stations. Toyota and Honda are also investing in new fuel cell vehicles. In 2019, Toyota introduced the second generation of its Mirai fuel cell vehicle and started selling fuel cell buses. The company also plans to increase its production capacity for fuel cells from a few thousand to 30,000 units per year over the next year or two.

Japan Inc. is already exporting its fuel cell technology. Toyota is offering many of its patents at no charge and selling its technology in the global market. The Portuguese bus manufacturer CaetanoBus is sourcing its fuel cell system from Japan. The technology company Panasonic is marketing its fuel cells for household use in Europe through an alliance with the German heating technology company Vaillant.

The Olympic Games as Jump-Start for a Hydrogen Society

The Olympic Games are supposed to give the country’s hydrogen strategy an additional push, even domestically, as shown by two major projects launched by Tokyo’s city administration. By the start of the games, the city’s transportation agency intends to ramp up the number of hydrogen buses leased from Toyota from 15 to 70. With their blue exteriors and the words “Fuel Cell Bus” emblazoned on them, the buses are a clear advertisement for the integration of hydrogen into the Tokyo cityscape. The other project is the first of its kind. After the games, the Olympic Village will be converted into a city neighborhood with about 5,600 apartments. Takeshi Ikawa, Tokyo’s director of new development, pointed proudly to a line in the construction plan. “The first municipal hydrogen line in Japan will run here,” he said.

The pipes will start at a hydrogen filling station north of the district, where hydrogen is separated from natural gas. From there, it will takes a subterranean course over a few hundred meters to two fuel cell parks with an output of nearly 40 kilowatts. They are designed to supply a local shopping center and public facilities with electricity and hot water. Panasonic is also equipping 4,000 condos with small fuel cells. Ikawa said the objective is clear: With this new city district, Tokyo intends to show the world what a megacity might look like with sustainable climate policies.

More Stories About E-Mobility