Obtain news and background information about sealing technology, get in touch with innovative products – subscribe to the free e-mail newsletter.

17.05.2017 | Story

"Anyone who is afraid won’t be innovative”

Many companies like to see themselves as dynamic and innovative – but innovation doesn’t automatically arrive on cue. Dr. Jan Kuiken of Freudenberg Sealing Technologies (FST) and Management Professor Charles O’Reilly talk about available and required resources, and the ideas kept in drawers.

Mr. Kuiken, how far ahead can someone look into the future?

Kuiken: He can look infinitely far ahead, but how relevant is what he sees there? Some time ago, we had a project whose objective was to look 35 years into the future: How is demography developing? What will the main trends be? This was a wonderful experience for writing a science fiction novel. But which of the scenarios from the genre’s great novels actually have any business relevance? A few, at most.

So that means looking ahead too far is not really helpful?

Kuiken: Sure, it can be a great help, but just two to three years is a realistically manageable timeframe in a real business environment. And even that is uncertain. Who predicted the financial crisis of 2008/09? So what we need is the absolute flexibility to adapt as well as a look into the future. A mere two years is too short a timeframe for a long-term development. In our department, we have now determined that we want to look ahead nine to ten years. What trends could there be? We are focusing our development resources on that.

Mr. O’Reilly, you do research on innovation and why companies fail at being innovative. Is ten years a reasonable timeframe?

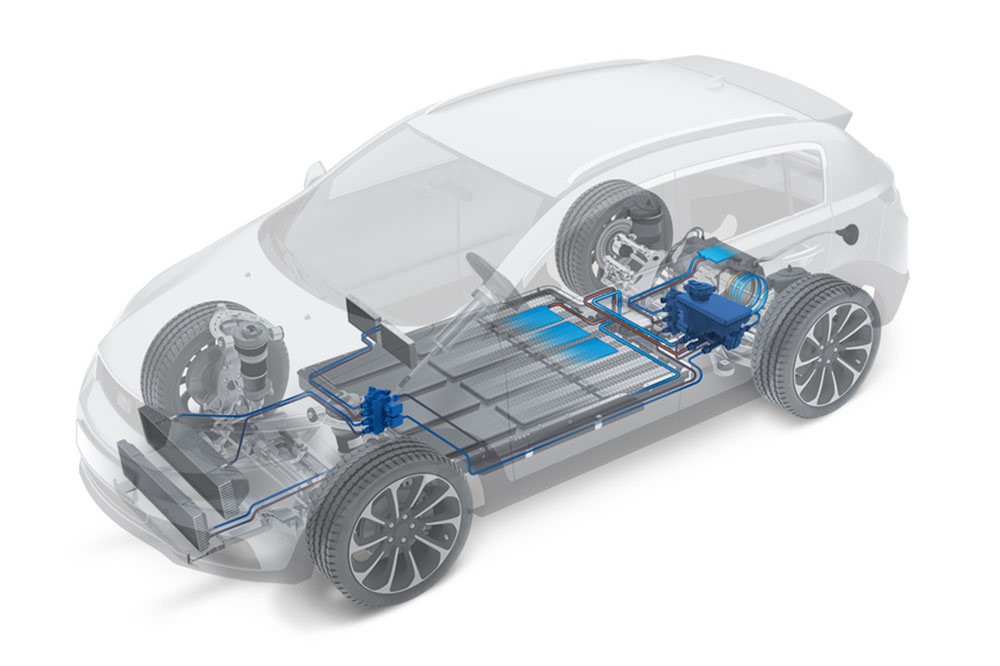

O’Reilly: To begin with, every industry has its own rate of development. Anyone presiding over a major automaker knows change is coming, in the form of autonomous driving or new powertrain technologies. And he also knows that this will happen within the next decade. The change will proceed more slowly for an oil company. For many IT companies, it is impossible to forecast even the next two years. So the crucial factor is that you identify the change and roughly assess what could happen – even if no one knows exactly when. And, in our opinion, it follows that companies should experiment.

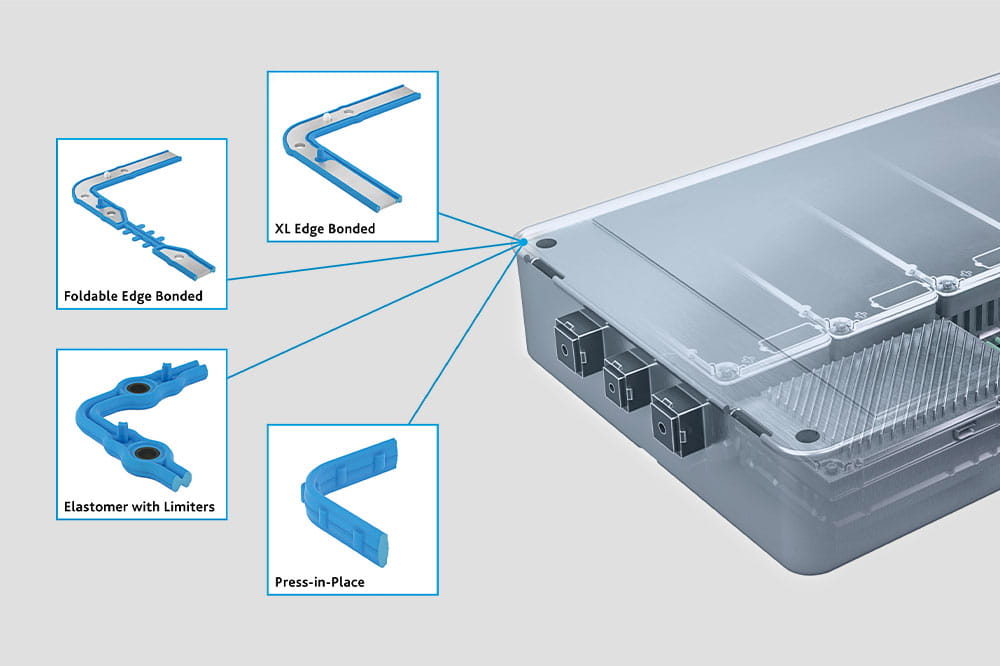

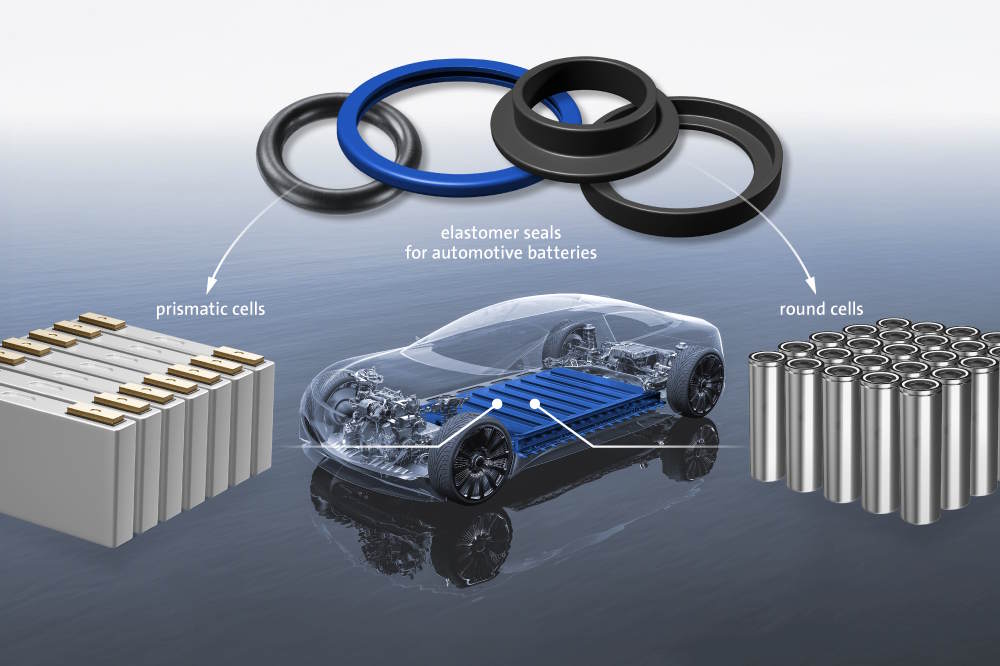

Kuiken: I’m in complete agreement. Let’s take electric mobility. Even three years ago, many people were still saying that it sounds good, it will certainly happen – at some point. At FST, we dealt with it early and have begun preliminary work, on lithium ion batteries, for example. The real upsurge has not yet happened, but we have the appropriate ideas for coming years in our drawers.

Mr. O’Reilly, in your latest book, you vividly describe how many companies fail at innovation because it requires time and resources.

O’Reilly: Yes. And this is very logical to start with. Many companies feel they are under financial pressure. They think rather short term. Even investors and shareholders. are not necessarily interested in costly experimentation. They can invest their money directly in startups. In addition, successful companies in particular have spent a great deal of time and energy in establishing themselves in the forefront of their earlier business field. Why should the company risk its short-term success when its long-term success is not guaranteed in return? A great deal depends on management, on the will to move in this direction.

That is one of the central theses of your studies: Leadership is crucial. If you want to be innovative, you need a persuasive executive at the head of the company who takes the lead.

O’Reilly: But here we are not talking about leadership style, which can take many different forms. We have worked with a great number of companies, and one of them was Cypress Semiconductor, a semiconductor manufacturer. The executive had a rather authoritarian style and handled many things personally. But he encouraged innovation. Another example is DaVita, which was involved with dialysis. But it was practically bankrupt at the end of the 1990s. CEO Kent Thiry was an entirely different type of manager, much more accessible, but it was his willingness to experiment that was crucial. I see leadership as the capacity to do what makes the company successful while managing experimentation for the future. DaVita is a comprehensive health care company today, and Cypress has founded new startups such as solar cell manufacturer SunPower. In this way, both have developed entirely new fields for themselves.

Mr. Kuiken, do you see parallels here in the way that Freudenberg Sealing Technologies is no longer focusing solely on seals for lithium ion batteries?

Kuiken: We have had a change in thinking. Until now, we have focused strongly on components, but we are meanwhile increasingly thinking in terms of systems. The knowledge for this is based on our experience with materials, but it goes beyond that – in the direction of electromagnetic shielding, for example. There are questions that we are asking ourselves: How do we bring this to market? What could the future business fields be? Take stack seals as an example. In this case, I need a seal with an operating life of more than ten years, in a highly aggressive and corrosive environment. We have already done preliminary development work on this. And now customers are slowly coming around and formulating more and more specific requirements for their batteries.

But that requires backing from the company’s leadership.

Kuiken: Yes, and we are in a very good position here thanks to our new CTO Dr. Ted Duclos. He is encouraging us to come up with even more ideas. In some cases, we have so many already that we have to work our way through them first. But by filling our drawer with ideas and innovative projects, I am promoting an increase in value – that is to say: We at Freudenberg Sealing Technologies are prepared for the future. The money that we have invested is not gone as long as I know where my drawer is.

O’Reilly: I would definitely not say that every penny invested will be paid back on a one-to-one basis, but that is not what this is about: As academics, we sometimes undertake sensible research yet still fail in the end. This kind of failure often opens up new prospects.

Innovation demands self-persuasion?

Kuiken: Yes. No inventor who ever took an idea from its nucleus to market readiness would say it was easy. At the same time, self-doubt is always part of the experience. Ultimately, I am entering new territory. It is impossible to see the path in advance. This is a frame of mind. What does the marshmallow challenge tell you? It involves groups of people being asked to build a tower out of spaghetti, thread and a marshmallow. And what type of group regularly scores the best? Not the engineers, but rather primary school children. They have the courage to just keep trying. Failure is a learning process.

So failure isn’t bad?

Kuiken: No. If you are afraid of failing, you won’t have the capacity to innovate. If you want to find the solution by just circling the problem, you will only find a solution that you were already familiar with. Our task is not the description of the problem. And as experts, we must not merely stand at the edge and offer tips. We have to be fully involved. We have to be ready to fail. Otherwise, I’m like a football spectator who yells out how the team should be playing. If I want to make changes, I have to be part of the team.

O’Reilly: This matches our research results. It is certainly true that, when you invest in innovation, there are always plenty of reasons to bring the experimentation to an end. This is not a problem at the start. Playing mental games costs nothing. But as soon as potential, real-life projects emerge from the ideas and need resources, they are halted surprisingly often. IBM once found that it had developed but never commercialized 29 technologies that are successful today. The reason: At the time, it lacked a culture that supported innovation. Instead, the departments all ended their development work to protect their profit margins.

A counter-question: An innovation has to be successful in the market, doesn’t it?

Kuiken: Of course. Engineers sometimes tend to choose the most challenging solution. They end up with a product that all the customers enthusiastically praise as wonderful and extremely interesting – but say they don’t need it. Or it’s too expensive.

O’Reilly: A good idea is not yet an innovation. The question is whether you can actually implement it. In fact, it is often not the pioneers who are successful with an idea in many cases. It is those who follow in a targeted way. Innovation alone is no guarantee of success.

This takes you to the continuation of the interview. A shortened version has been published in the current edition of our customer magazine ESSENTIAL.

More news on the subject Automotive & Transportation

Join Us!

Experience Freudenberg Sealing Technologies, its products and service offerings in text and videos, network with colleagues and stakeholders, and make valuable business contacts.

Connect on LinkedIn! open_in_new