Obtain news and background information about sealing technology, get in touch with innovative products – subscribe to the free e-mail newsletter.

23.05.2017 | Story

"The future is not a straight line“

In the first portion of the interview, Dr. Jan Kuiken of Freudenberg Sealing Technologies (FST) and Management Professor Charles O’Reilly discussed how innovation affects companies. In the second portion, they talk about the balance between old and new, radical ideas, and the optimism of innovation experts.

Mr. Kuiken, in the first part of the interview, we discussed innovations that were ahead of their time. Has FST come up with an innovative idea in the past, that had to lie in a drawer for a long time because the market wasn’t ready for it?

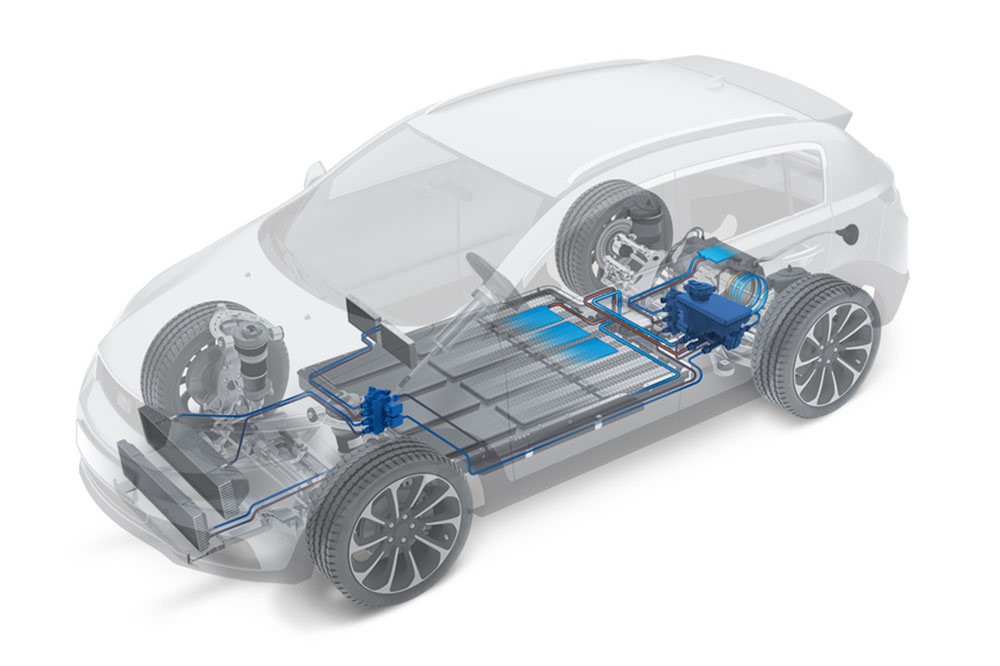

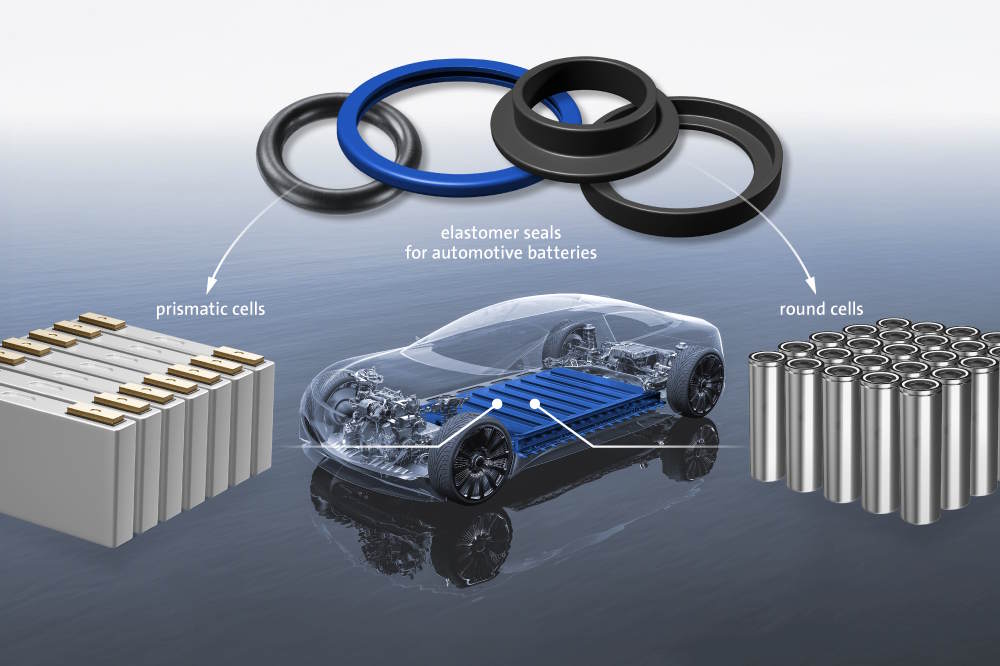

Kuiken: Levitex is one example. We developed the basic concept ten years ago. But the industry did not yet see the need for it. CO2 reduction was certainly an issue, but the manufacturers used their own standard solutions to deal with it. Then came the diesel scandal, which reshuffled all the cards. Incidentally, the exciting question is: which area is developing more rapidly and dynamically: the reduction of pollutants in internal combustion engines – or e-mobility?

FST is working on both fields. Isn’t that schizophrenic?

Kuiken: No, on the contrary. I always have to think in terms of scenarios. The future is not a straight line. There are always various possibilities.

O’Reilly: Very appropriate image. I see things the same way.

Kuiken: We have to make sure that we have the solutions in our drawer. The crucial job of a research and development department is deciding what fields should be tackled. In the end, our resources are naturally limited. At FST, we have developed the Innovation Management System for just this purpose. It divides the ideas into categories: “bread-and-butter,” “pearls” and “white elephants.”

O’Reilly: I haven’t heard it put that way before, but I really like it. We use a couple of other models and grids. For example, “innovation streams.” In a matrix, you can categorize whether a company is active in new or old markets or is operating with new or familiar technologies. New technologies in new markets is the most revolutionary and high-risk variation.

Mr. Kuiken, in the first part of our interview, you used the image of drawers that you constantly fill with ideas. How many drawers does FST have?

Kuiken: A great many. Forgive me for saying so, but that’s why we are the market leader. The potential is huge. Our mentality has to be: “Saying it won’t work is not an option.” By the way, people are often especially innovative when resources are tight. It is no cliché to say it is possible to capitalize on crises. They have to be used. Think back to 2008/09 when 50 percent of the auto industry’s revenue collapsed. And yet some companies emerged stronger – including us, incidentally. Crises and disruptive changes are also an opportunity. You just have to be prepared for them. That’s our approach and we are in a position to do that.

O’Reilly: But here I would make a qualification: When they are in the midst of a crisis, companies sometimes no longer have the resources to make a variety of bets on the future. That is often important. Not every idea works. It is better to get started when things are going well for the company.

Your main thesis is that companies must maintain a balance between successful products and new products. The term that you have come up with is “ambidextrous.”

O’Reilly: The core business and new experiments play according to completely different rules. Values and conventions that are responsible for making a company a success in its core business can become obstacles in the new business. In our studies, the companies that have shown themselves to be successful innovators almost always had a spatial separation between the core business and innovative projects. But, at the same time, there was permeability so the young contenders could benefit from the strengths that they lacked such as sales and accumulated knowledge. Plus an overarching vision and values. This is anything but easy. Personally, I am fascinated again and again at how companies are able to walk this tight rope.

Kuiken: It does a company good to think completely differently once in a while. Most of our innovations are rather incremental. In the case of really radical ideas, we must ask ourselves: Why is this radical? What do we want to do with it? Like the idea of being able to extract all the ingredients for a seal out of a few cubic meters of air.

To me that sounds very radical.

Kuiken: Doesn’t it? When my boss told me about it the first time, I just looked at him in disbelief. But this naturally puts us squarely into a discussion of ecological footprints. With our products, we want to make a contribution with sustainable goods and with materials that can be recycled. Material innovation is very important to us.

O’Reilly: That actually works?’

Kuiken: A year ago, it still sounded quite insane. Then we started to do the research and today it already sounds less radical.

But no company can support itself on radical ideas alone.

O’Reilly: There are companies that have been very successful at selling innovative ideas when were not able to execute them themselves. Sometimes a company hasn’t got the sales structure or the chance to market innovations itself.

Kuiken: Let me stick with this image briefly: If I only have radicals in a chemical process, then I have chaos. But radicals still move around in the system. If I completely forget the system, meaning my own company, then I am heading in the wrong direction. The ultimate goal must always be to move the company forward. Take molecular modeling as an example: Today, it is still impossible to calculate complex molecules comprehensively, so they cannot be simulated in a meaningful way for certain processes. But that will come. It would offer us enormous advantages in material development. It is still very far off, but we are closely watching what is happening and looking at the particular computational models that are being researched. If we were to apply these models in a practical way, we could alter materials even more effectively to bring out fully targeted effects. For example, reduced friction or superlubricity. Reduction will definitely be a trend. This is a classic example of an innovation that looks far into the future while keeping the present in view.

How do you balance that?

Kuiken: With the company culture. There are plenty of companies where innovation is not even valued. Conversely, I have to ask myself as an engineer who has worked for 35 years on an issue but hasn’t made any headway at all: Why? The responsibility for this balance rests with each of us. Earlier, there were definitely questions: What do the people in the research department actually do? The ones in their ivory towers who don’t produce anything at all. But this has changed at our company because we are involved.

You’re very optimistic, aren’t you?

Kuiken:If you, as an expert on innovation, are not optimistic, you have a problem. Anyone who wants to think in terms of solutions must have a positive attitude, and this does not contradict being realistic and self-questioning. But why should anyone act halfheartedly? In the end, it just takes a connection between advanced development, the business areas and sales to find out what the customers need.

O’Reilly: I think one of the reasons that the “design thinking” approach has been so successful is that it captures this precisely. Everything starts with the customer. It is a matter of fulfilling the customer’s unexpressed desires. There are many examples of companies that have stumbled over the fact that they did not understand what their customers really wanted.

When you look at the histories of successful companies, you realize that many of them don’t even make what they originally started out with.

O’Reilly: The British aviation and auto supplier GKN started out as a coal mining firm more than 250 years ago. Ball Corp. is a 136 year-old global producer of cans, but one of its main pillars is now in aerospace technology. The list goes on. I admit that I was not familiar with Freudenberg beforehand. The story of a tannery that manufactures seal rings from leather scrap and then makes the leap into new materials is a wonderful example.

So is it possible that FST will no longer be producing seals in 50 years?

Kuiken: Yes, it’s possible that we will then be building systems or providing services. Why not? But if we proceed as we have done until now, we will definitely still be around. This conviction is anchored very deeply in the organization. Because we know from our history that we were always in the position to keep going. If you look back 150 years, you see so many crises and revolutions: the oil crisis, the world wars, the technological developments.

O’Reilly: That is very wise. And very appropriate. IBM has missed out on ground-breaking developments, but the company got its act together in a very impressive and instructive way. It generates a large portion of its revenue today with services and software – and no longer with hardware.

Kuiken: Now we are back at the start of our discussion: looking ahead is only helpful if we are prepared to adapt. You have to be ready to move in new directions.

More news on the subject Automotive & Transportation

Join Us!

Experience Freudenberg Sealing Technologies, its products and service offerings in text and videos, network with colleagues and stakeholders, and make valuable business contacts.

Connect on LinkedIn! open_in_new