Obtain news and background information about sealing technology, get in touch with innovative products – subscribe to the free e-mail newsletter.

08.11.2022 | Story

Ongoing Transformation

Freudenberg’s history is replete with examples of how new materials have fueled the company’s progress: from leather to elastomers and modern plastics. Importantly, each material decision the company has made since its founding in 1849 has provided a stepping stone to the next decision and has guided the company’s response to changing markets, economics and even resources. This is a story of how not to be deterred by crises.

Patent leather marked the starting point. In the mid-19th century, the trend spread across Europe. “Everything that was supposed to look beautiful was made with patent leather,” said Dr. Michael Horchler, Head of Corporate Archives at Freudenberg: “Shoes, bridles, even sofas.” And fire department helmets. The patent leather varnish made them more flammable, “but they looked good”, said Horchler. Producing patent leather required expert knowledge of varnish and a deep understanding of leather. One German tannery was well positioned to capitalize on the trend. Its owner, Carl Johann Freudenberg, had always emphasized quality and ideas. In combination, which meant material expertise. “He had a high standard of excellence,” Horchler said. For the first time, the tannery began to develop in new directions.

Of Sheep and Bees

Varnish was the focus of what may have been the first employee innovation in Freudenberg history: Once it was lacquered, leather was placed in a field so it could dry in the sun, but when the varnish hardened, it suddenly had unwanted yellow stripes. This was a conundrum until an employee offered an idea: Buy a herd of sheep. The problem was that bees had gathered pollen from the clover growing in the meadow and then had crawled over the leather, leaving yellow pollen behind. When the sheep devoured the clover, the bees began looking for greener pastures.

Engine for Growth, Economic Shock

Leather production was complicated at the time: It took about 75 steps just to process a raw hide into finished leather. Freudenberg relied on skilled craftsmen to perform these steps; the company still lacked machinery at that point in time. “If you wanted a good product, every step in the production process had to be optimized”, said Horchler. This carried over to the company philosophy, the archivist and company historian pointed out. “Material expertise must always be open to innovative ideas”, he said.

Patent leather became the first great engine of the company’s development. By the mid-1870s, thanks to this line of business, the company had risen to become one of Germany’s largest leather producers. When chrome plating was introduced in 1900, Freudenberg expanded to become the largest leather maker in Europe and one of the largest in the world – and held that position until the end of the 1920s. Then came the shock. With the arrival of the global depression, the leather market collapsed. New markets were desperately sought to secure the company and avoid the dismissal of several hundred employees.

“Changing to Be Successful”

Salvation came in the form of seals. At the time, seals were made of impregnated felt or leather. Their production required knowledge of materials as well as lubricants such as oils. Once again, materials expertise was in demand, and Freudenberg could provide it. “Leather is a highly resistant material,” Horchler said. “But without a coating, it doesn’t stay leakproof for long.” In the case of leather seals, the company’s expertise with patent leather carried the day. One development led to another. The company was already selling its first leather seals by 1929. One admonition from Carl Johann was ever-present, Horchler said: “It takes the capacity to change to be successful in the long run.” So, the company continued to experiment. In 1932, it combined leather with metal, and the Simmerring® was born. Walther Simmer built a spring into a metal housing to adjust the amount of pressure required for different sealing applications. Its spring simultaneously held the seal against the rotating shaft and secured the seal lip within the metal housing. For the first time, radial shafts could be sealed really well. “That was Freudenberg’s great breakthrough in the seals business.”, said the archivist.

Rubber Becomes a Competitive Advantage

Although leather remained an important material in Freudenberg’s seal production well into the 1950s, leather wasn’t the only material being courted by the company. Early efforts with elastomers were initiated in the 1930s, since leather was in short supply starting in 1934. The National Socialist Party took control of the country in 1933, and it wanted the domestic economy to be as self-sufficient as possible. Natural raw materials were suddenly scarce, forcing Freudenberg to search for acceptable leather substitutes. As a result, the company’s chemists and scientists became some of the first industrial experts to work with synthetic nitrile rubber. The composite material was a mixture of nitrile, sulfur and carbon black that became dimensionally stable when vulcanized. “That is why seals are often black,” Horchler explained. Despite – or perhaps because of – a scarcity of materials, Freudenberg found a solution that also expanded its materials expertise. A steady flow of elastomer compounds followed.

“We were the absolute pioneer with the first rubber seals,” Horchler said. The German auto industry became the company’s most important sales market. But Simmerrings, bellows and O-rings from Freudenberg were also used in machine-building. The new material was a big hit: “Rubber can be shaped more precisely and easily than leather,” Horchler said. This made it possible to adapt seal lips to unique application requirements. Freudenberg’s elastomer seals quickly set themselves apart from the leather seals of its competitors.

Within a century, Freudenberg’s use of materials had moved from leather to synthetic elastomers. And that ensured its survival. “Only one or two of the major tanneries of the 1920s still exist today,” Horchler said. Critical to the company’s longevity and success, Horchler noted, was its determination to stay very close to its original business.

Innovations Keep Coming

The years of the German economic miracle showed just how rewarding the investment in elastomer research was. More and more people were able to afford cars, and the German machine-building industry was exporting products abroad. “Those were the real boom years for seals,” Horchler said. Freudenberg’s product line grew and continues to grow to this day. The company currently has about 200,000 elastomer compounds available in its materials portfolio, thanks to a continual focus on innovation. “There were a great many failed attempts during the early years of elastomer research,” Horchler acknowledges. “But even if they didn’t always work out at first, something good often emerged in the end.”

Dr. Michael Horchler

Dr. Michael Horchler has worked in the Freudenberg Group’s Corporate Archives for more than 20 years. He took over management of the collection in 2008. A historian, business manager and media researcher by training, Horchler joined Freudenberg during his doctoral studies. He is passionate about his profession. “Unlike many historians who specialize in defined timeframes, we work on a living thing. Our history continues to be written. We deal with the company’s past, present and future,” he said.

That’s the impressive aspect of material innovation. Again and again, important solutions seem to emerge by accident. For example, because Freudenberg had expertise in the interplay of elastomers and metals, it was able to build components that reduce vibration and noise. A new line of business, vibration control technology, arose. “Today’s auto industry would be inconceivable without vibration control technology,” Horchler said. Nonwovens became a Freudenberg product line in much the same way. Originally a carrier material for latex synthetic leather, they have now become a key component in cars, clothing and shoes, and in medical and technical applications such as wound dressings, batteries and wiring systems, they are also used in Vileda cleaning products. But there is more to the story: “Nonwovens burned through development funds for a decade”, Horchler said. Yet the research continued. This is not just characteristic of Freudenberg – it is explained by the company’s history.

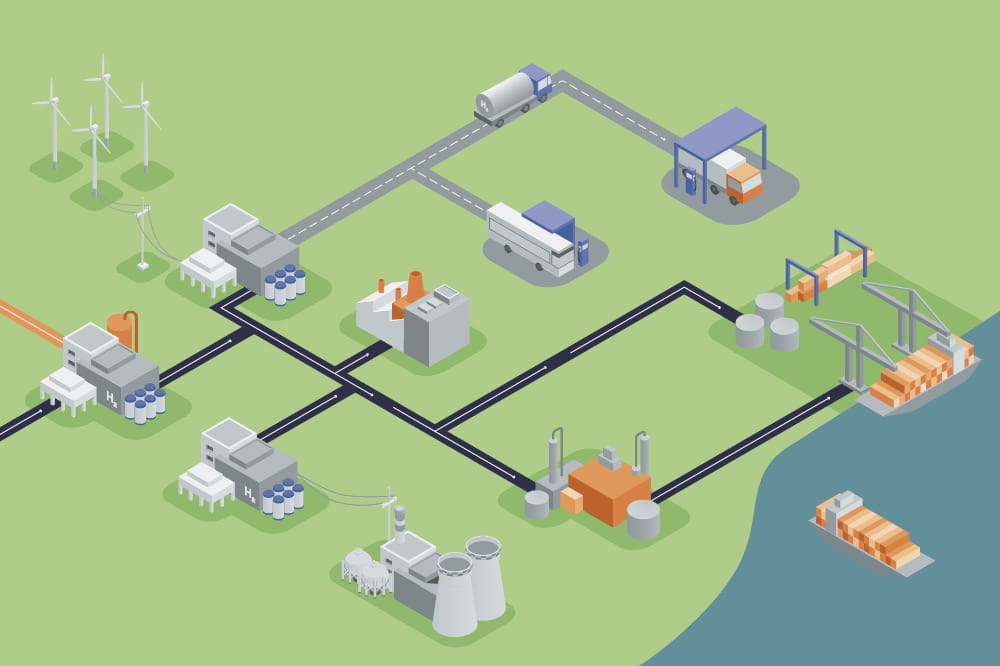

“The company was always on the lookout to see what new raw materials were available in the market,” Horchler said. When in doubt, the company looked at each crisis as an opportunity to develop further – just as the first leather seals emerged from the emergency created by the global depression. “Today the production of seals has its own corporate division – Freudenberg Sealing Technologies”, said the archivist. In 2002, after the leather business had proved unprofitable for years and output had fallen to low levels, Freudenberg bid farewell to this founding material. But not before a modern, innovative, knowledge-based company was secured.

More news on the subject Sustainability

Join Us!

Experience Freudenberg Sealing Technologies, its products and service offerings in text and videos, network with colleagues and stakeholders, and make valuable business contacts.

Connect on LinkedIn! open_in_new